The Life Sciences Report: You have said that the pharma drug discovery model is broken, and have written about this extensively. Would you describe your thesis?

Mark Kessel: The number of new chemical entities that have come out of big pharma's research and development (R&D) pipeline has been anemic in recent years. There are a number of reasons for this. One is the bureaucracy that has resulted from the growth of these companies and the number of people who have to sign off on various projects, which has tended to stifle innovation. Big pharma has resorted to various models to improve results, but when you look at those results, I'm not sure that they've all been successful. Big pharma has recognized that the R&D model isn't what it used to be. That's my fundamental thesis.

TLSR: What strategies or models have the big pharmas used to ramp up research and development?

MK: They have resorted to various models to improve results, using independent or autonomous divisions. For instance, Eli Lilly and Co. (LLY:NYSE) created Chorus as an alternative R&D group in 2002, and then Pfizer Inc. (PFE:NYSE) created its Biotherapeutics and Bioinnovation Center in 2008. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK:NYSE) decided that it would in-license about 50% of its R&D budget rather than go it alone, which is a very significant amount. Back in 2001 Glaxo also restructured its R&D model, creating its Centre of Excellence for Drug Discovery (CEDD).

TLSR: Mark, the pharmas are caught between a rock and a hard place in some ways. Instead of putting retained earnings back into research and development, they have to pay a dividend to investors. Otherwise, people won't invest in these very large companies, which are just too big to grow. Did we allow pharmas to get too big?

MK: I'm not sure that size alone is the issue. There's another thought. Over the years a number of observers and commentators have suggested that big pharma should limit its focus to drug development and get out of early R&D activities—that they should do the large, phase 3 trials. They're better able to do worldwide trials than smaller companies, and they also have the extensive global sales organizations to commercialize products. I think they ought to leave the early R&D to the more nimble biotech sector.

TLSR: The odds are stacked against a drug entering a phase 1 trial—about one in 10 makes it to market. The length of time and costs are much worse if you're inventing a new platform like Isis Pharmaceuticals Inc. (ISIS:NASDAQ), which got FDA approval for its antisense drug, Kynamro (mipomersen sodium), on Jan. 29. Your firm, Symphony Capital, financed that product's development at one time. After two decades of excruciating research and development, Isis is just now getting a drug on the market, and only for a very narrow indication, homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, which occurs in one in one million births. Does the case with Isis demonstrate the weakness of a shareholder-funded model for developing platforms, or even drugs in the small biotech company setting?

MK: This is an interesting case. Yes, Kynamro was funded by our firm, and Isis bought the drug back from us. We believed in that technology platform. The drug was approved for a narrow indication, but I suspect Isis is going to try to move it into broader indications for lowering cholesterol.

But to get to your specific question, the biotech sector is in a crisis, in the sense that raising capital to advance the development of new platforms has become increasingly difficult. I'm not sure how much Isis has spent over the years, but I'm going to guess it has been well north of $1 billion ($1B). That's probably just shareholder capital, and not capital that came in through licensing or partnering opportunities.

"The idea is to make an investment in a project rather than in a biotech company itself."

When I first started providing financing opportunities for the biotech sector, there were a fairly small number of companies around. Today there are many more companies, and they are seeking a finite pool of capital. Although there seems to be a little bit of daylight in the initial public offering (IPO) market right now, it has not been available in a robust manner for years. Also, the long cycle associated with developing drugs doesn't fit the venture capital model very well, given the time horizons. Other sources of capital are available, but they're not nearly enough to fund the biotech industry.

TLSR: I don't think you could repeat that model today, for instance, with Isis. Could you?

MK: I'm not certain that Isis would be able to repeat the same $1B capital raising in today's environment. Biotech companies today have to use a different model, and not seek to become commercial companies, even though the returns to investors would be enhanced if small startup companies were able to maintain their birthrights to their drugs. You might be able to repeat an Isis today, but you would have to find some novel ways to finance it, and it's increasingly difficult to achieve that.

TLSR: What sorts of different financing models might we see? Are there any novel ideas being worked out?

MK: We have a couple of ideas working in favor of different kinds of financings, whether it's licensing or financing one-at-a-time drug development. Some of the contract research organizations (CROs; companies that do clinical trials for pharmas) were investing their own money into programs. And the big pharmas, as their pipelines continue to be relatively anemic, are looking at orphan drugs. Companies may be able to get a commercial compound with fairly attractive economics through the orphan drug route, which is cheaper and faster. Genzyme (now a unit of Sanofi [SNY:NYSE]) did that, for example, with Ceredase (alglucerase injection) for Gaucher's disease, but that was not exactly a slam dunk. A lot of the technology came from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), at the government's expense. Unfortunately, a lot of the sources of capital that came from NIH and other agencies for earlier-stage development have diminished because of the economic meltdown.

"I think big pharma ought to leave the early R&D to the more nimble biotech sector."

To develop drugs today, companies need to think more critically and strategically about how they're going to get long-term capital because the venture guys who have been in these companies 5–10 years or more need to exit. Even the IPO market is limited, because it takes a while for venture capitalists to get out of their investments. They're looking for merger and acquisition (M&A) exits. The M&A exits provide value for late-stage compounds, and a lot of acquisitions don't give companies credit for earlier-stage compounds. Companies are giving away a lot of value.

It's going to be more difficult, but companies need to look at more creative financings. That's why the Symphony Capital model was successful. There were a lot of opportunities available, and we were providing a unique form of collaborative financing that was fairly competitive with other sources existing at that time.

TLSR: In his State of the Union address, President Obama spoke about investment in science, and specifically in brain science. Now, with an aging population, a lot of families are starting to feel the stresses of dementia and other diseases, such as Parkinson's disease. I couldn't help but think about the Dwight D. Eisenhower model of developing our superhighway system in the U.S. This was done without regard to a return on capital, because it was deemed a national emergency during the Cold War, when the President felt that we needed roads to move around the country. I'm wondering if we need something like that now—a national movement in healthcare to develop drugs. It is exceedingly difficult to develop murine or other animal models for cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer's disease. You can measure tumor progression, but how do you measure cognition in a rodent? Don't we need something big?

MK: I totally agree with you. First, let me touch on the issue of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other forms of dementia. Our collaboration with Lexicon Pharmaceuticals Inc. (LXRX:NASDAQ) included a drug for cognition. We used mouse models to test the efficacy of the compound. We abandoned that trial after an intended indication did not show the kind of efficacy we were looking for in the mouse. We recognized that challenge early on.

"The biotech sector is in a crisis, in the sense that raising capital to advance the development of new platforms has become increasingly difficult."

In 2009 I wrote an article for Nature Biotechnology called "The Lifeline for the Biotech Sector." In that article I proposed that the federal government do something along the lines of what you suggested—but in a way that might get some traction—by allowing biotech companies to benefit from their net operating losses. That is one "asset" they all have. The idea was that they could monetize those losses through tax credits. The idea actually did not get traction, but it was flipped into the $1B tax credit, which was more palatable to Congress. The Qualifying Therapeutic Discovery Project tax credit was enacted as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. The credit targeted therapeutic discovery projects that showed a reasonable potential to result in new therapies to treat areas of unmet medical need, to prevent, detect or treat chronic or acute diseases and conditions, to reduce the long-term growth of health care costs in the United States, or to significantly advance the goal of curing cancer within 30 years. All of these goals were funded by such a minor sum compared to what was offered in government bailout programs to the financial sector.

The economics of government investment in this sector are very compelling. If you look at the period from 1970 to 2000, gains in life expectancy added over $3 trillion ($3T) per year to national wealth. Half of that came from the advances in heart disease alone.

A 1% reduction in mortality from cancer alone would have a present value to current and future generations—and here I am speaking of Americans only—of about $500B. If we ever achieved a cure for cancer, the value would be something like $50T. The government is not focused on the tremendous leverage achieved. That $1B tax credit was really a pittance.

TLSR: In 2002 you co-founded the private equity firm Symphony Capital. Could you describe your model and what you do?

MK: Back in the mid 1980s, I invented a form of financing to assist in advancing earlier-stage compounds, and it was used by the most successful companies—Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc. (acquired by Johnson & Johnson [JNJ:NYSE] in 1999), Genzyme (acquired by Sanofi in 2011), Alza Corp. (acquired by Johnson & Johnson in 2001) and a host of others.

"It's going to be more difficult, but companies need to look at more creative financings."

The idea was to do two things. One was to provide capital so companies could do better clinical trials than they could on their own. Symphony would totally fund drug development so companies could do robust trials, not based on a cash-burn rate they could afford, but on what made sense for the efficient development of the drug. The other part of our thesis was that some of the companies were very good at discovery, but they had never really developed a compound. We thought by providing drug development expertise, we could greatly enhance our investment.

The way our model worked was fairly simple. We would create a company—let's call it Symphony Development Co.—which would in-license two or more drugs from a biotech company. We would commit a specific amount of capital designed to take the drugs through proof of concept, and we would give the company the right to buy back the drugs at a predetermined price. That's what we did with Isis and its drug Kynamro. If the drugs failed we would be at risk, and the biotech company would not have to buy them back. If the drugs were successful, their value should exceed the buyout price. That was the fundamental model used in all of our investments. We were not investing in the companies themselves. We were making a structured-finance investment based upon the assets that we were going to further develop.

TLSR: So, you do project funding.

MK: Exactly. We do structured project financing. Bells and whistles are associated, which are a little different, but the idea is to make an investment in a project rather than in a biotech company itself. We have a strategic alliance with RRD International, which is a drug development consultancy firm. The firm helps us with the diligence, and representatives serve on our joint development committees with the biotech companies. We can be objective as to whether a trial is failing, whether it is worthwhile to put more money into the development program, or whether we should use some of the capital to expedite trials by opening up more centers to enroll patients faster. Those are the kinds of decisions we make, based not so much on the cost of money, but on what would be the best and fastest way to develop a drug and get better results.

TLSR: So RRD International serves as a consultant to help a science-driven firm take a program to a therapeutic end. Is that what we're talking about?

MK: Yes, that's basically it. The people working with us are high-quality professionals who have conducted more than 400 FDA trials. They help formulate the drug development plans and the regulatory strategy with us, and they provide program managers, but they do not do the commodity CRO work. They don't go into hospitals to recruit patients and that kind of activity.

TLSR: I understand that your model is project financing, but do you ever take an equity stake in companies?

MK: The fundamental model is to fund just the projects. With Isis, we created Symphony GenIsis Inc., into which we put $75 million ($75M), and Isis licensed three compounds to us. We then went ahead and spent the cash on development of those programs. Johnson & Johnson came to Isis and was attracted to two of the programs we were developing with Isis. Isis bought back our portfolio company, which had the three drugs that we had licensed from them, plus the remaining cash. It then paid the buyout price pursuant to the purchase option. At the time we did the deals we would get some equity in the companies we worked with, in either warrants or stock, giving us a little bit of upside and some downside protection for our investments. But the principal model was the way you described; it was project financing.

TLSR: Can we go ahead and talk about a couple of these companies that were or are portfolio projects of yours?

MK: I'll pick a few that had different outcomes. Let me start with Exelixis Inc. (EXEL:NASDAQ). We invested $80M in a collaboration with Exelixis for three compounds, XL647, XL784 and XL999 (which we abandoned due to toxicity issues). When it came time for Exelixis to decide whether it wanted to repurchase XL647 and XL784, it became economically prohibitive for it to do so due to the cost of taking XL647, which had achieved proof of concept in phase 2, through two phase 3 trials. Its stock declined during that period of time, from around $1.2B to $600M. The buyout price and cost of doing the phase 3 trials would have approached something on the order of $200M. So Exelixis passed. We now own those drugs.

"The economics of government investment in this sector are very compelling."

We have since out-licensed XL647 for oncology. We also out-licensed XL647 for polycystic kidney disease, an indication that we identified and that was not part of the Exelixis' focus. We also discovered that XL784 had potential to be a blockbuster drug for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and we filed patents for that indication. We are now in the process of seeking to license that drug. That is an example of a portfolio company that didn't get purchased by the collaborating biotech company.

We have already discussed Isis—it went the complete cycle. Isis investors did very well through our collaboration, as did our own investors when we were bought out.

Lexicon was a $60M collaboration for four drugs: LX6171 (for AD); LX1031 (for irritable bowel syndrome [IBS]); LX1032 (for carcinoid syndrome); and LX1033 (for IBS). Lexicon bought us out, and we have the right to future payments associated with the drugs that we financed.

We did a $50M collaboration with Alexza Pharmaceuticals Inc. (ALXA:NASDAQ), which Alexza bought back. One of the drugs, Adasuve (loxapine), has been approved for acute agitation. The other drugs we financed, AZ-004 and AZ-002, were for migraine and panic attack, respectively.

Those are three different models, if you will. I can go into others as well, but that is a snapshot of our investments.

TLSR: You've also made an investment in OXiGENE Inc. (OXGN:NASDAQ). This company has really had a difficult time. The market cap is down in the $7M range. Can you talk just a little about it, please?

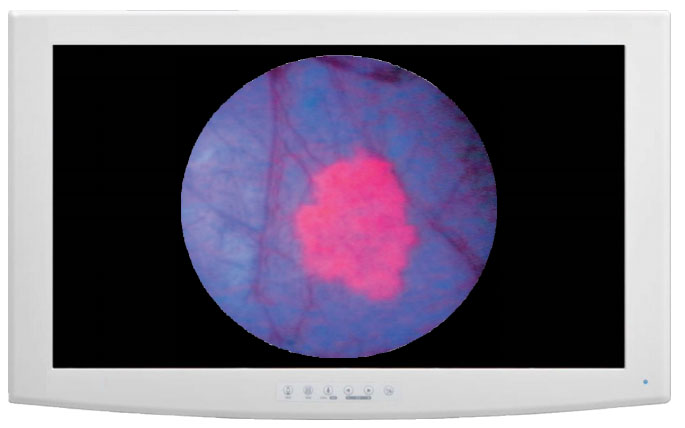

MK: We made a $30M investment, focusing on its Zybrestat (fosbretabulin) for cancer and ophthalmology. The drug is a vascular disrupting agent that is being developed for thyroid cancer. The company also has OXi4503, a second-generation cancer drug that was also part of our original collaboration.

Then OXiGENE bought us out for stock in the company. Yes, it's been a difficult struggle, but Zybrestat is a very interesting agent. The company needs a good dose of capital because it is targeting an orphan indication, and so enrollment is slow. As a topical agent Zybrestat is being pursued for ophthalmology.

TLSR: You have also invested in Dynavax Technologies Corp. (DVAX:NASDAQ). Can you comment on that?

MK: In the Dynavax situation, we invested $50M in three drug candidates: 1018 ISS for cancer, and second-generation ISS for hepatitis C and for a hepatitis B therapeutic. Dynavax bought our company for stock, warrants and a note. Dynavax had a PDUFA date on Feb. 24 for its hepatitis B vaccine, Heplisav, and got a complete response letter (CRL) with regard to safety in such a broad age range, from 18–70 years, and also because novel adjuvants may cause autoimmune events. The stock took a tumble.

TLSR: Mark, cash is fungible, so how do you make sure the money goes where it is intended—to development of the drug that you own?

MK: We structure these deals so that we enter into a drug development agreement with the companies. To the extent that they do work on behalf of our projects, we reimburse them for their full-time equivalents on a fully burdened basis. In effect, they get paid for doing the work for us.

Most of the money we invest goes out of house—to CROs and clinicians. But if companies advance drugs through their own internal resources, we reimburse them for that. If a company manufactures its own drug, we have a manufacturing agreement with them, and the company is responsible for continuing to provide the drug. In the situation with Exelixis, the drug was manufactured by an outside entity. We got all the rights to that, the patents, the know-how, etc., and we continued to advance the drugs ourselves. It is done through contractual arrangements.

TLSR: It was a great pleasure speaking with you, Mark. Thank you.

MK: Thanks very much, George. I very much appreciate your very thoughtful questions, covering a lot of topics in a relatively short period of time.

Mark Kessel co-founded Symphony Capital LLC, a private equity firm investing in the clinical development programs of biopharmaceutical companies, in 2002. He is widely recognized as the leader in structuring product development investments for the biopharmaceutical industry. Kessel was formerly the managing partner of Shearman & Sterling, with day-to-day operating responsibility for one of the largest international law firms. He received a bachelor's degree with honors in economics from the City College of New York, and a juris doctor magna cum laude from Syracuse University College of Law. Kessel is currently of counsel to Shearman & Sterling, and a director of Dynavax Technologies Corp., the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics and Fondation Santé. He also served as a director of the Biotechnology Industry Organization, the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development, OXiGENE Corp., Antigenics Inc., Heller Financial Inc. and Harrods (UK) Limited and as a trustee of the Museum of the City of New York. Kessel has written on financing for the biotech industry for Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, Nature Biotechnology, The Scientist and other publications, and on issues related to governance and audit committees for such publications as The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, The Deal and Euromoney.

Want to read more Life Sciences Report interviews like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you'll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Streetwise Interviews page.

DISCLAIMER:

The views expressed are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firms with which he is affiliated.

DISCLOSURE:

1) George S. Mack conducted this interview for The Life Sciences Report and provides services to The Life Sciences Report as an independent contractor. He or his family own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview: Isis Pharmaceuticals Inc.

2) The following companies mentioned in the interview are sponsors of The Life Sciences Report Johnson & Johnson. Streetwise Reports does not accept stock in exchange for its services or as sponsorship payment. Johnson & Johnson is not affiliated with Streetwise Reports.

3) Mark Kessel: Symphony Capital LLC, of which I am a partner, owns shares or has the right to receive future payments from the following companies mentioned in this interview: Alexza Pharmaceuticals Inc., Dynavax Technologies Corp., Lexicon Pharmaceuticals Inc. and OXiGENE Corp. I was not paid by Streetwise Reports for participating in this interview. Comments and opinions expressed are my own comments and opinions. I had the opportunity to review the interview for accuracy as of the date of the interview and am responsible for the content of the interview.

4) Interviews are edited for clarity. Streetwise Reports does not make editorial comments or change experts' statements without their consent.

5) The interview does not constitute investment advice. Each reader is encouraged to consult with his or her individual financial professional and any action a reader takes as a result of information presented here is his or her own responsibility. By opening this page, each reader accepts and agrees to Streetwise Reports' terms of use and full legal disclaimer.

6) From time to time, Streetwise Reports LLC and its directors, officers, employees or members of their families, as well as persons interviewed for articles and interviews on the site, may have a long or short position in securities mentioned and may make purchases and/or sales of those securities in the open market or otherwise.